Metabolic syndrome is a term applied to a collective group of risk factors that raise the risk of other health conditions, regardless of being a horse or human. In humans, we see a rise in the risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, vascular disorders, neurodegenerative conditions and many others. In the horse, we generally see an increased risk for insulin resistance, Cushing’s disease, and laminitis. The term ‘metabolic’ actually implies an alteration in cellular metabolism or biochemical processes, but is often quickly associated with a state of increased body weight or obesity. Equine metabolic syndrome is actually very complex, involving many pathways. The higher your level of understanding the easier the condition is to manage.

Metabolic syndrome in both people and the horse is on the rise. In the United States, the rates of obesity have doubled in the past 10 years, as have the increased incidence of associated medical conditions. The cause is complex and often attributed to hereditary factors, highly processed foods, overconsumption of fat calories and lack of exercise. In the horse, the rise is similar with more metabolic equine patients being diagnosed every year, often attributed to the diet, low exercise levels and hereditary factors. In my equine consulting practice, metabolic syndrome plays a role in about 50% of cases, whether the owner is aware of the condition or not. Overall, the condition of metabolic syndrome is becoming more prevalent in both humans and animals.

In humans, it has been estimated that 25% of adults have metabolic syndrome to some degree, which increases the risk of developing diabetes by 5 times. It has also been estimated that 80% of all diabetics actually succumb to cardiovascular disease, which is a common consequence of metabolic syndrome. In humans, risk factors for developing metabolic syndrome include:

- Large waistline

- High triglycerides

- Low HDL

- High blood pressure

- High fasting blood glucose

For sake of discussion in the horse, we can apply a ‘large waistline’ or overweight body condition, the high fasting blood glucose, and often the elevated insulin levels to most cases of equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) as risk factors.

You have to understand that this is a ‘syndrome’ or collective grouping of risk factors, which together lead to the increased risk of development of other health conditions. Given that it is a ‘syndrome’, there is no one factor that causes the condition, but more so interdependent on many factors, working together, which essentially set the stage. If we can grasp this concept, then we realize two things:

- First, no “one” thing is going to solve all of the problems (this is a biggie)

- Second, by seeing all factors involved, it opens the door for increased possibilities and approaches for management.

Obesity or an increased body mass is viewed as being central to the development of metabolic syndrome, which leads to increased morbidity and mortality in all species. Fat or adipose tissue is actually active in a sense, some viewing it as an active endocrine organ, secreting adipokines (leptin, adiponectin) and cytokines (TNF-alpha, IL-1), which can then impact both local and systemic inflammation. Essentially, research tells us that in regards to inflammation, an overweight person, or animal, actually is more ‘inflammatory’ in nature because of this fact, thus predisposing to a host of health conditions. 1

In people, we often make an association with metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes, which is indeed correct. However, type II diabetes is a result of a progression of the condition or syndrome over time. In fact, type II diabetes is the stage in which the patient demonstrates elevated blood glucose or sugar levels, particularly when fasted. Insulin resistance is actually a precursor to full development of type II diabetes, in which the body is unable to utilize insulin properly, for various reasons, which over time will lead to improper management of sugar or glucose, resulting in high levels.

This progression of equine metabolic syndrome over time is what is important in my eyes, as a veterinarian, as often we fail to miss the key indicators or road signs along the way. Unfortunately, by the time we make the diagnosis, actual disease is present and we missed seeing the warning signs.

This is evident in people that are overweight, which is often recognized by both patient and doctor, but relative importance is not given to it. Over time, we not only have an overweight person, but elevation of triglycerides, lowered HDL, blood pressure concerns, elevated insulin, elevated HbA1C. Then a diagnosis of type II diabetes, cardiovascular concerns, and other health issues develop. It is a matter of progression.

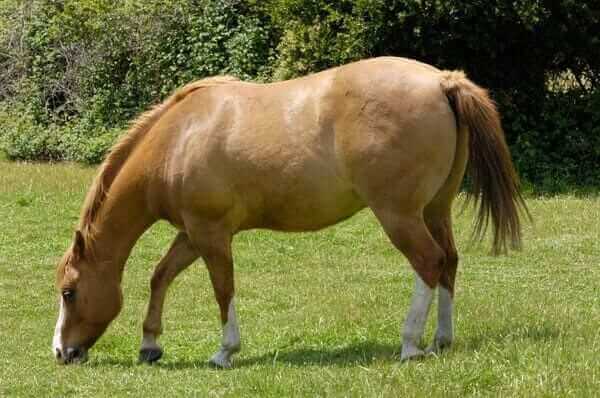

In the horse, we see an overweight patient with a higher than normal body condition score, which is typical of some breeds. Many owners remark that they’d like to see a horse with some fat on his/her ribs, which is fine to an extent, but we have to keep in mind that the events are progressive. One year, that technically overweight horse is fine, then the next, we find that they are having a hard time navigating the pastures and coming up lame with the spring grass. In the early stages, your veterinarian may perform blood work which indicates normal glucose/sugar and insulin levels, but yet we have active signs of laminitis. The diagnosis of equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) may be brushed off to an extent and the patient treated symptomatically. Then, as time progresses, we have continual patterns of clinical or subclinical laminitis in that horse, an increasing overweight body condition, and now elevated fasting glucose and insulin levels. In fact, with time, many equine metabolic syndrome patients actually develop Cushing’s disease or PPID, which again can be seen as a matter of disease progression.

Insulin resistance is the failure of tissues to adequately respond to insulin which is circulating in the blood stream. This development of insulin resistance is directly tied in and linked with ongoing inflammation. Insulin is needed to move sugar or glucose into the cell for energy production, thus when insulin is not functioning correctly, glucose or sugar levels will rise. Insulin resistance is just one factor that develops and contributes to metabolic syndrome. It is a complex pathway of development, linked back in most cases to an overweight body condition, excessive fat or adipose tissue, inflammation generation, altered glucocorticoid metabolism, oxidative stress and release of adipokines, all of which contribute to altered insulin signaling and binding to receptors. The interesting part of an overweight body condition is that the relative distribution of fat also appears to play a role. In humans, especially males, the accumulation of excessive body fat in the abdomen tends to increase the relative risk of cardiovascular disease. In horses, the accumulation of fat along the neck crest appears to be directly connected with metabolic syndrome. For an unknown reason, fat in these locations appears to be more ‘active’ in nature, likely contributing to higher levels of inflammation, cytokine and adipokine release. 1

In the horse, one of the biggest consequences to metabolic syndrome is the concern of laminitis which can be devastating. Laminitis secondary to metabolic syndrome is somewhat different than that of other pathways. In metabolic syndrome laminitic cases, the condition seems to wax and wane, develop slowly in most instances and of variable degrees. In many of these EMS (equine metabolic syndrome) cases, the condition of laminitis is often contended with over many years. In comparison, development of laminitis secondary to grain overload or infection (endotoxemia) is more acute and severe in nature, occurring quickly and rapidly, often with much higher pain levels and a poorer outcome.

Laminitis associated with equine metabolic syndrome is believed to be primary to vascular dysfunction or blood flow disturbances, with the inflammatory process being secondary. The increased and prolonged elevation of insulin levels itself is strongly connected with vascular dysfunction and blood flow disorders.2 In comparison, a horse that develops laminitis secondary to grain overload or infection is usually directly correlated with an acute inflammatory reaction within the body, which then equates to a more rapid and progressive event. In fact, it even appears that metabolic syndrome induced laminitis appears to impact different areas of the foot or hoof tissue itself, as compared to purely inflammatory induced conditions. It is worthwhile to note that over 90% of horses presented with laminitis have underlying metabolic concerns.

One of the interesting things to me, as a veterinarian and researcher, is the connection between stress and metabolic syndrome in the horse. When the body is responding to a stressor, the hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated, which triggers the production and release of several hormones. The end result of concern is the production of cortisol by the adrenal glands. Cortisol is a glucocorticoid and has anti-inflammatory properties, needed to help the body to adapt to stressors in the short term. In the long term, under long term stress conditions, cortisol can actually be harmful to the body as it is a catabolic steroid by nature. Human research indicates an increased tendency towards weight gain when the body is under chronic stress, which may be accounted by some having an increased tendency to eating when stressed. This also applies to some cases with horses. When we look at any health condition, metabolic syndrome or any of its consequences, when the body is not healthy, it is often under stress to some level. Stress is a natural response, attempting to help the body to cope or adapt.

The interesting thing here is cortisol and the long term impact on health, when chronically released and elevated.

There is a direct association between prolonged elevation of glucocorticoids (cortisol) and an increased tendency towards fat deposition, high glucose levels, type II diabetes, vascular dysfunction and metabolic syndrome development. Persistently elevated glucocorticoid levels are also tied in with myopathy (muscle disorders), menstrual disturbances, osteoporosis, osteonecrosis, mental disturbances and decreased immune function.3 The most interesting thing here is that under normal circumstances, there is a feedback loop within the HPA axis, meaning that under normal circumstances of short term stress, when the body produces enough cortisol, it feeds back and tells the hypothalamus and pituitary to shut down the further stimulation of the adrenal gland. So, really, the body is trying to stop the negative destruction of ongoing or persistently high levels of cortisol. However, this does not always happen and there are bypass loops. When the body is under chronic stress and fails to adapt, the HPA axis is persistently activated, failing to shut down, leading to high cortisol levels on a routine basis. In other situations, inflammatory cytokines including TNF-alpha, IL-1 and IL-6 can also activate the HPA axis, without the pure stress response by the body being required. What this reveals to us is that often this can become a viscous cycle of events, usually starting with a stress response, leading to weight gain, inflammation development and then the inflammation development pushing the cycle further on its own.

It is interesting to note that a chronically active HPA axis often demonstrates inadequate suppression by dexamethasone, meaning that the feedback loop that is normally present is not working properly. This is important, for in cases of suspected Cushing’s or PPID cases in horses, we rely on high doses of steroid administration to tell us whether that HPA axis is working properly, and if it is not, most commonly we diagnose Cushing’s disease. This may be incorrect in some horses, especially the younger group which may be more stressed than we’d like to believe. If they are indeed stressed, leading to dysregulation of the HPA axis, then the lack of a normal response to dexamethasone may not actually indicate Cushing’s disease and a need for Pergolide therapy, but more so indicate a chronically stressed patient, in need of a different approach.3

There are many genes regulated by glucocorticoids, like cortisol. In some cases, we have upregulation or activation of genes, while in others, we have down regulation or shutting off of genes. Genes often encode for proteins that are used in cellular signaling, function and metabolism, not to mention inflammation regulation. Some genes that are upregulated by glucocorticoids include leptin, Glut-4 and gluconeogenesis or release of sugar by the liver. Leptin is viewed as the ‘satiety’ hormone, helping to regulate the hunger drive in the body.3 In cases of obesity, it has been noted that there is actual leptin resistance which develops, similar to insulin resistance, in which case cells do not respond adequately to the leptin, thus hunger or appetite can go unregulated.5

On the other side of the coin, we have genes that are downregulated or shut down as a result of glucocorticoids. These include POMC (appetite control), Adiponectin (insulin signaling), Osteocalcin (bone metabolism), thyroid hormone (metabolism) and production of some cytokines including TNF-alpha, IL 6 and 8.3 Again, as in other cases, we can see the vicious cycle that can occur, secondary to prolonged elevation of cortisol, contributing to weight gain, obesity, insulin resistance, potential hypothyroidism and even bone metabolism concerns.

In the end, metabolic syndrome and all of its risk factors are directly tied in with inflammation on some level, as well as closely being tied in with stress and the stress response. In fact, obesity has been defined as a disease of chronic, low grade inflammation.4 The process is complex, but overall I hope that you can further see not only this complexity, but also the fact that there are many players in the game, many contributors. There are many approaches to therapy, which we will discuss in a future article, but one thing is important to remember. Most of these therapies are only approaching or managing one small facet of the process, which makes a more ‘broad spectrum’ approach more realistic and desirable. In the case of humans, we can utilize oral sugar lowering or hypoglycemic agents, designed to help us void excess sugar in our urine, but this is only one small part of the entire process and really does not address the CAUSE of why that sugar is elevated. In other cases, we have oral medications, such as Metformin, which have demonstrated abilities far beyond just that of managing blood sugar levels, which is promising. Even diet, which may seem inconsequential to many, is at the surface only addressing one contributor, such as helping us to manage weight, but in fact may actually be addressing multiple pathways by providing nutrient and antioxidant support and reducing intake of harmful contributors such as food additives. Exercise is one factor that all too often is overlooked and neglected, both in people and horses, as well as pets. Exercise is beneficial on many levels, from helping us to manage stress, to reducing body weight, to increase overall fitness, cardiovascular health, reducing inflammation and even improving the body’s response to insulin.

We can’t just say to that overweight person, improve your diet and get some exercise. Likewise, we can’t just take that metabolic syndrome horse with insulin resistance and think that sticking them in a dry lot with reduced intake of nutritious forage is going to solve that problem. It is more complex than this and unless we see it and address it appropriately, we will be like a dog chasing his tail.

If we understand the process, even on a basic level, then we can see how utilizing just one mode of therapy, whether it is pharmaceutical, herbal or even dietary can be beneficial but also restrictive on the same level. Often, to get the results we are desiring, a combination approach, addressing multiple pathways provides the best results.

Thank you.

Tom Schell, D.V.M.

Nouvelle Research, Inc.

www.nouvelleresearch.com

References:

1. Morgan, R et al. Equine Metabolic Syndrome, Vet Rec, 2015, Aug 15: 177(7);173-79.

2. Venugopal, CS et al. Insulin Resistance in Equine Digital Vessel Rings: An In-vitro Model to Study Vascular Dysfunction in Equine Laminitis. EVJ 43: 744-49

3. Paredes S, Ribiero L. Cortisol: The Villain in Metabolic Syndrome, Rev Assoc Med Bras, 2014, 60(1), 84-92

4. Moller DE, Kaufman KD. Metabolic Syndrome: A Clinical and Molecular Perspective. Annu Rev Med, 2005, 56; 45-62

5. Pan H et al. Advances in understanding the interrelations between leptin resistance and obesity. Physiol Behav, 2014, 130: 157-69